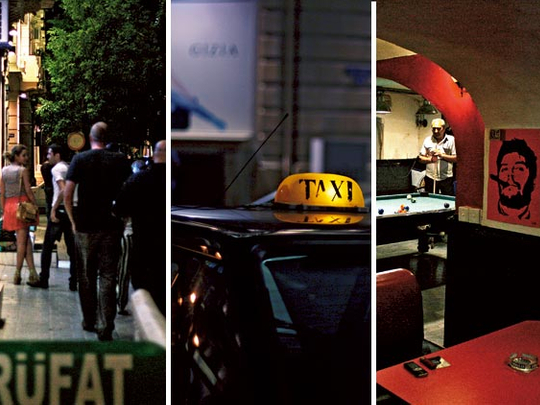

It’s past the midnight hour and I’m in a hole-in-the-wall Soviet nostalgia bar, awash in the red of the former USSR flag and strangely, Manchester United. Stalin, Lenin, Khrushchev and even Yuri Gagarin – the first man in space – stare down disapprovingly as Skid Row’s I Remember You rises above the din of bar conversation. This is a world away from the hip nightclubs mentioned in travel guides, not the venue that put Baku on Lonely Planet’s list of hedonistic cities to visit this year. But if you are scouring for remnants of the Soviet Union in Baku; you couldn’t have asked for a better place in Azerbaijan’s capital city.

“I routinely get ridiculed for running a bar that pays homage to our Communist past. Clearly, there are many people here that don’t want anything to do with our Soviet heritage,” says the owner of the bar, Alex Ghusenov, as he arranges a Communist-era matryoshka doll set, depicting the Soviet Union’s leaders on the bar counter. “There’s plenty from the Soviet era that we can be proud of. Many forget that we were among the top countries in the world then. That’s not something I want to erase from my memory.”

Azerbaijan, once a remote outpost of the Soviet Union, is only now streaming back into the collective consciousness of the world. At the turn of the last century, before the country was invaded by the Soviet Union, Baku was a thriving city of oil barons who built opulent mansions overlooking the Caspian Sea. Art and culture flourished thanks to the opera houses and theatres that oil wealth funded. After the First World War and the Soviet invasion in 1918, everything changed. By the time the Soviet Union had crumbled, Azerbaijan was just a forgotten enclave

in the Caucasus.

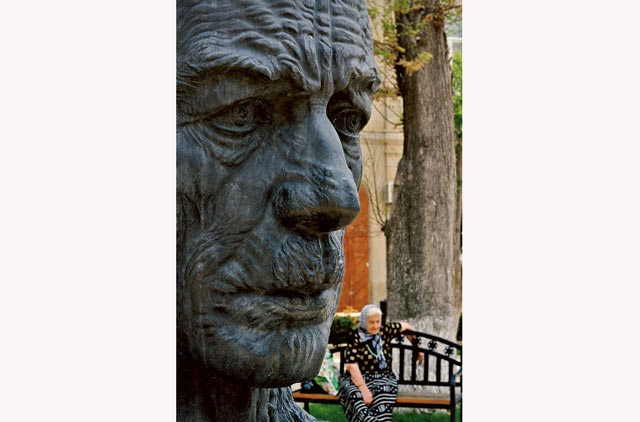

Today, Baku is very much a city in flux, a city with many moods. Parts of it – mainly around Fountain Square – look like they could be neighbourhoods in any city in Western Europe what with tree-lined avenues, designer boutiques, hip nightclubs and fashionable cafés. But there are other parts that remain true to the city’s Turkic traditions – a walk around the walled Old City (Ichari Shahar) is reminiscent of the meandering streets of Istanbul’s Sultanahmet district or Beyoglu. Though most buildings and monuments from the Soviet era have been razed to the ground to make way for modern glass towers and hotel complexes, relics from the Soviet days still remain. You’ll find everything from dull, concrete five-storey apartment blocks – a legacy of Khrushchev’s housing scheme – to the more imposing House of Government (formerly called the Palace of the Soviets).

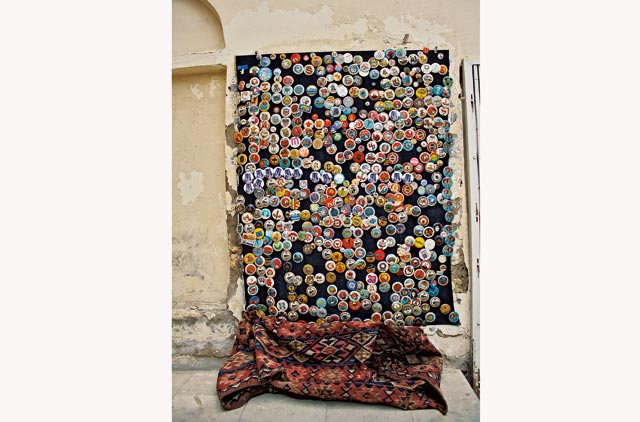

Azerbaijan’s history is inextricably linked to the story of petroleum. One of the oldest oil-producing nations in the world, in the early 1900s Baku produced half of the world’s oil. During the Second World War Adolf Hitler made a strategic play to capture the city and seize the oil fields in the Caucasus, but the Germans were beaten back after the Battle of Stalingrad. Today, scouring souvenir shops in Ichari Shahar will yield old Wehrmacht service medals that can be bought for around 40 Azeri manat (Dh190).

Let Ichari Shahar – a Unesco World Heritage Site – be your first marker on the tourist trail. Start at the mysterious eight-storey Maiden Tower, said to have been built around the sixth century. My guide says it was once a medieval observation tower, but there are many historians who say the tower was originally built as a defensive structure. Today it houses a museum and also hosts an annual Maiden Tower International Art Festival that attracts participants from all over the world. Climb to the top of the tower for sweeping views of the city that include the Baku Boulevard, the Caspian Sea and the Flame Towers... but more on that later.

Built in the 12th century, Ichari Shahar’s winding cobblestone streets, sandstone houses, quaint restaurants, carpet shops and tea houses (cay evi) are richly atmospheric. Lada cars jostle for space with gleaming new Maseratis in these narrow streets – the former, a vestige of the city’s Communist past and the latter, proof of the city’s new wealth. The area is also home to the 15th-century Palace of Shirvanshah, the ancient seat of the rulers of Azerbaijan. Be warned, tourist information is scant and English is not widely spoken, so do your homework before you set out.

Stop for lunch at Mugam Club, a 16th-century caravanserai a stone’s throw from the Maiden Tower. A caravanserai is a roadside inn where travellers stopped to rest during their journeys along the ancient trade routes. Mugam’s courtyard, dominated by a fragrant fig tree, serves as the main dining area. Azeri cuisine is similar to Turkish fare – so expect to tuck into kebabs, baba ganoush and salads.

A ten-minute walk from the Old City takes you to a younger, hipper Baku. Start at the Ichari Shahar metro station and walk north on the Istiglaliyyat Street, an arterial road that runs through most of Baku’s central uptown. Walk past the magnificent Ismailia building. Built in the Venetian Gothic style, at first glance the building looks like a cathedral, but it’s actually the Presidium of the Academy of Sciences. Walk on to Fountain Square, the beating heart of downtown Baku. This public square is a major tourist attraction and is lined with boutiques, expat bars, restaurants and souvenir shops. It is a great place to shop for Soviet-era military badges, medals and campaign ribbons. The Azeris are a friendly bunch, so don’t hesitate to haggle. If you think the place is buzzing during the day, wait until you see it by night. It’s not for nothing that the city has earned itself a reputation as the region’s party capital.

The new Baku is a gleaming cosmopolitan city that’s been propped up by the country’s oil wealth. This summer, Baku hosted the Eurovision finals at the bling new Crystal Hall, a sport and concert complex. The Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre with its flowing lines – the handiwork of Zaha Hadid – is now as much a symbol of the new Baku as the Maiden Tower is of the old. A clutch of five-star hotels and luxury resorts have opened up in the last few years and many more are set to open in the coming months. In May this year, Dubai-based Jumeirah Group opened its first resort in the capital – the Jumeirah Bilgah Beach Hotel. The new Baku obviously looks up to Dubai as evidenced by the tripartite Flame Towers. The three glass-tower complex is set to be completed this year and one of the towers will be home to Baku’s first Fairmont hotel.

However, everything in the new Baku is not shiny and new. Despite being a Constitutional Republic, Azerbaijan has mostly been run by one family since independence in 1991. Heydar Aliyev, the self-styled father of the nation was president for close to a decade until he was succeeded by his son, Ilham Aliyev in 2003. A lot of buildings, especially on the drive into the city from the airport, have impressive facades, but the back of the buildings tell another story. A drive out to the coastal settlement of Bilgah, about 40km from the centre of Baku, offers some interesting insights. For most of the drive, both sides of the motorway have four-metre high sandstone walls. At first glance, they seem like the walls of gated communities designed to keep out unwanted visitors, but a closer look reveals that they were built to hide slums. Behind these walls, you can catch glimpses of unpaved streets and dilapidated buildings. When I asked about them, my taxi driver replied, “The walls are meant to hide our poverty. Tourists don’t need to venture beyond them.”